Getting those butterflies to fly in formation

Standing on the beach, at the start of my very first half ironman; mouth dry, pulse raising, stomach a flutter; my sister vocalised precisely what I was feeling. She turned to me and said: “My butterflies are flying way out of formation”. I have since discovered that this phrase has been used several times and has been attributed to a number of people but I will always accredit it to my big sister! The most oft quoted is by Rob Gilbert: “It’s all right to have butterflies in your stomach. Just get them to fly in formation.”

Everybody gets nervous. Feeling anxious is the body’s normal reaction to stress. For example, feeling butterflies in your stomach before a class presentation or nervous before a competition are normal experiences. Experts say nervous butterflies are both a psychological and physical experience that can be traced back to our body’s evolutionary fight or flight instincts. This sensation causes us to respond to problems head on, or retreat to our place of safety. Imagine you came face-to-face with lion while on a walking safari in Africa. In that split second you know you are in a dangerous situation. When faced with this imminent physical danger, or even a perceived threat, your body’s sympathetic nervous system triggers the “fight-or-flight” response. This response prepares your body for emergencies by increasing your heart rate, widening your airways, releasing large amounts of glucose from the liver and shunting blood away from the gut. The blood is redirected toward the muscles in the arms and legs which makes them ready to either defend you, or run away faster.

However, this acute shortage of blood to the gut does have side effects — slowed digestion. The muscles surrounding the stomach and intestine slow down and the blood vessels specifically in this region constrict, reducing blood flow through the gut. This reduction in blood flow through the gut in turn produces the oddly characteristic “butterflies” feeling in the pit of your stomach. It senses this shortage of blood, and oxygen, so the stomach’s own sensory nerves are letting us know it’s not happy with the situation.

So how do we get those butterflies to fly in formation and make that stress to work for us?

The body reacts to a primal influx of cortisol and other stress chemicals that urges you to fight or flee the unknown. And since running away isn’t really a good solution to modern-day stress, it is important to explore techniques to manage it. It is also important to realise that the body also reacts to perceived threats. If you don’t perceive something as a threat, there is generally no threat-based stress response. It is possible to change your perception of some of the stressors in your life. Accurate assessment and subsequent reframing is a skill, this shift can change your experience of stress.

How to shift your perception of the threat

• Focus on the resources you have to meet the challenge

• Remind yourself of your strengths

• Develop a positive mindset

Hans Selye introduced the concept of stress having two categories: distress and eustress. Distress is stress that negatively affects you and eustress is stress that has a positive effect on you. Eustress is what energises us and motivates us to make a change, to strive to do better, reach further and work hard. In a way, stress helps your body to prepare to face challenging moments or danger ahead.

Eustress and Distress

Eustress, or positive stress, has the following features:

• Motivates, focuses energy.

• Is short-term.

• Is perceived as within our coping abilities.

• Feels exciting.

• Improves performance.

Distress or negative stress, has the following features:

• Can cause anxiety or concern.

• Can be short- or long-term.

• Is perceived as outside of our coping abilities.

• Feels unpleasant.

• Decreases performance.

• Can lead to mental and physical problems.

Changing our response to stress

Australian behaviour change expert Alison Earl, suggests the ROAR approach to change our response to stress.

• Recognise what’s happening in your body when you feel stressed (think of physical sensations of stress as energy to be harnessed.)

• Owning the opportunity to intervene and influence your response

• Activate the energy: “What can you do right now to use this energy in the service of your goals?”

• Recharge and reward. This is so important after a period of high stress to rebuild your resilience.

Stress and Performance

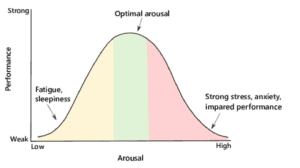

Balancing stress is easier said than done. A low-stress state can lead to apathy, while a high-stress state can lead to anxiety. However, being in the right “zone” of stress can lead to peak focus and productivity. The Yerkes-Dodson law is a model of the relationship between stress and task performance. It proposes that you reach your peak level of performance with an intermediate level of stress, or arousal. Too little or too much arousal results in poorer performance (see below)

Yerkes-Dodson Law of arousal and performance

Low arousal: no butterflies

Having no stress at all isn’t necessarily a good thing in terms of performance. For example, when your job is all about routine and nothing ever changes, boredom sets in. There’s no stress, but there’s also no motivation. You’re not being challenged and have no incentive to go above and beyond. Your work feels meaningless, so you do the bare minimum.

Optimal arousal: Butterflies flying in formation

A moderate level of stress goes a long way. It’s manageable, motivational, and performance enhancing. Your heart beats a bit faster. You feel a sense of clarity and alertness. Your brain and body are all fired up. It’s the rush you get before you run out onto the pitch, or that maths test that you have prepared so well for. It’s that extra little push you need when a hard deadline looms and you’re up for a promotion. There’s something you want, and a moderate surge of stress will boost your performance.

High arousal: Butterflies flying out of formation

In some situations, stress and anxiety are ramping up to an unmanageable level. Your heart may beat faster, but it’s unsettling, distracting, even nerve-wracking. You’ve lost focus and you’re not reaching your full potential.

When you butterflies are flying out of formation, there are a few things you can do that may help ease symptoms.

• Practice intentional breathing

• Reframe the feeling

• Accept uncertainty

• Challenge your negative thoughts

• Visualize positive outcomes

For many people, distress (stress and anxiety) can start to interfere with daily life and activities. If you feel as though the emotional or physical symptoms of stress are getting in the way of your daily life, then please do consult with a doctor or counsellor.

Bibliography

Book: Getting your butterflies to fly in formation – Ray Fretenburg

https://www.abc.net.au/everyday/changing-how-you-think-about-stress-to-be-less-affected-by-it/10824484

https://www.drake.edu/media/departmentsoffices/recreationservices/Distress%20vs%20eustress%20blog.pdf

Yerkes, R. M., & Dodson, J. D. (1908). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation. Punishment: Issues and experiments, 27-41.